BURNING BRIGHT

Teaching Drama 1963 – 1996

by

Frank McKone

Teaching Drama 1963 – 1996

by

Frank McKone

PART TWO

Interval One

In the Foyer 1966

Interval One

In the Foyer 1966

In this year I saw my first play to begin in a foyer: Rodney Milgate’s A Refined Look at Existence

(at Jane Street Theatre, University of New South Wales, directed by

Robin Lovejoy). While we were seated, waiting for action to begin, two

uniformed policemen looked in from the foyer, then went backstage and

appeared on the stage, clearly searching for someone. After scanning us

from the stage, they came in among the seats and arrested a man.

Despite claiming to be innocent, the man was rather forcibly removed to

the foyer, where his loud protestations had no effect and he was

apparently taken away.

Nothing else happened. House lights were still up. Nothing changed on the stage.

Suddenly behind us a wild looking bushman appeared, rifle pointed at the stage. A shot over our heads nearly deafened us. Somebody appeared on the stage, and only then did we begin to realise that the play had begun. Only later, when the well-known figure of actor Michael Boddy was present in the curtain call could we be sure that even the policemen in the foyer and the arrest were part of the fiction. Michael Boddy’s generous body shape was the final clue.

Teaching in Sydney was a bit too close to Head Office for me, but clearly drama was on the move as the National Institute for Dramatic Art got under way at Jane Street and then the Old Tote Theatre, while La Mama in Melbourne had already established the reputation of the new Australian ‘physical theatre’.

After a break from academia in Broken Hill, I had also decided to take on more study. This was not because I could expect more recognition (or salary) from the Department. If I had completed an Honours level BA degree, and then a Dip Ed, I would have begun teaching classed as five-year trained. With only a Pass degree and Dip Ed, I was classed as four-year trained. Five-year trained teachers began at second-year out salary. Because of my early hiccup, I came to Sydney for my fourth teaching year on third-year out salary and extra academic qualifications would not now change my salary progression.

But I had long wanted to follow up my special interest in Bernard Shaw, so I had proposed to Sydney University to enrol in an MA in literature for a thesis studying his novels and plays and to show them in the context of his philosophy. My proposal was accepted but I had to spend a year first in an MA Qualifying course to bring my qualifications to Honours standard. It was to satisfy this requirement, and my desire to understand Shaw, that brought me back to Sydney.

Where would I be posted? First to Drummoyne Boys’ High School. After Term 1 and our marriage in the May holidays, although the Department would not guarantee that my fiancée teaching in Coonabarabran (in north-west New South Wales) and I would be moved to schools near each other, my wife was moved to Bankstown Girls’ High and I to Homebush Boys’ High, both in Sydney. The schools were fairly near each other, but a long way across the city from where we lived, meaning an hour and half’s driving twice a day: but I guess, from the Department’s point of view, beggars can’t be choosers.

Three years of the Broken Hill culture did not prepare me well for the conservatism and lack of sense of humour at the Sydney schools. Though I did get to teach one senior class, I found the greater level of aggression quite depressing. Partly due to the sense of competition built in to Sydney culture, but even more because of the nature of single-sex boys’ schools, classroom teaching was not exciting for this year.

Drama could be found, but not of my kind at Drummoyne. I was immediately in strife since the young – hardly radical – men teachers and bank officers in Broken Hill had established the costume of shorts and long socks for work. My new Principal promptly informed me that only the Physical Education teacher was allowed to wear shorts, despite the heat and humidity of late summer in Sydney. But irony is always around the corner. The only subjects I was allocated to teach were English and ... PE! I still couldn’t wear shorts without time to change between 40-minute periods but, since I had never been trained to teach PE and was seriously concerned that I didn’t have the techniques to keep somersaulting teenagers safe, I conducted a term’s course in yoga.

The connection with drama might seem vague, but I had found that yoga breathing and concentration had been useful in the wings before going on stage. So my Drummoyne boys may not have gained much from PE, but I had the opportunity to explore more about yoga and to design exercises – which I hope also helped reduce a little of the city aggression. But, although I was transferred when we married without being consulted, I was glad: one term at Drummoyne was more than enough.

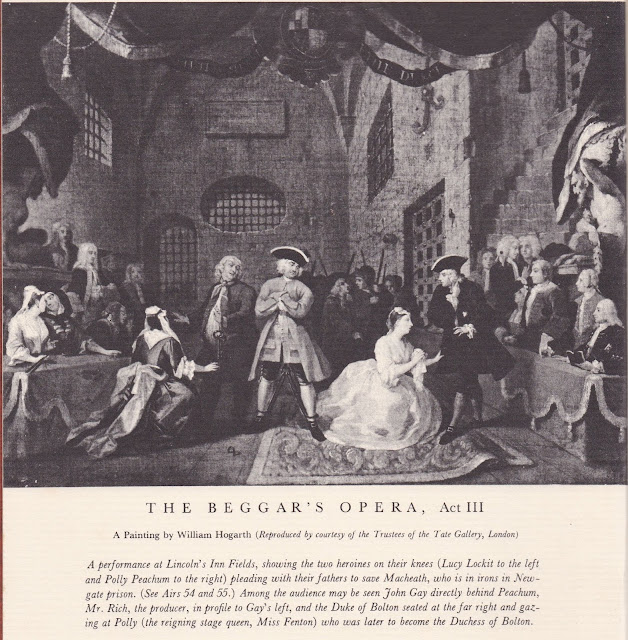

Homebush offered me a chance, as luck would have it, to take part in two drama events. The help Mr. Deamer gave in the production of the opera [The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay in the Benjamin Britten version]was greatly appreciated – we thank him and wish him all the best for his stay in Canada wrote students J. Lalchere and L. Pater in the school magazine, in which I am listed in the English Department.

Nothing else happened. House lights were still up. Nothing changed on the stage.

Suddenly behind us a wild looking bushman appeared, rifle pointed at the stage. A shot over our heads nearly deafened us. Somebody appeared on the stage, and only then did we begin to realise that the play had begun. Only later, when the well-known figure of actor Michael Boddy was present in the curtain call could we be sure that even the policemen in the foyer and the arrest were part of the fiction. Michael Boddy’s generous body shape was the final clue.

Teaching in Sydney was a bit too close to Head Office for me, but clearly drama was on the move as the National Institute for Dramatic Art got under way at Jane Street and then the Old Tote Theatre, while La Mama in Melbourne had already established the reputation of the new Australian ‘physical theatre’.

After a break from academia in Broken Hill, I had also decided to take on more study. This was not because I could expect more recognition (or salary) from the Department. If I had completed an Honours level BA degree, and then a Dip Ed, I would have begun teaching classed as five-year trained. With only a Pass degree and Dip Ed, I was classed as four-year trained. Five-year trained teachers began at second-year out salary. Because of my early hiccup, I came to Sydney for my fourth teaching year on third-year out salary and extra academic qualifications would not now change my salary progression.

But I had long wanted to follow up my special interest in Bernard Shaw, so I had proposed to Sydney University to enrol in an MA in literature for a thesis studying his novels and plays and to show them in the context of his philosophy. My proposal was accepted but I had to spend a year first in an MA Qualifying course to bring my qualifications to Honours standard. It was to satisfy this requirement, and my desire to understand Shaw, that brought me back to Sydney.

Where would I be posted? First to Drummoyne Boys’ High School. After Term 1 and our marriage in the May holidays, although the Department would not guarantee that my fiancée teaching in Coonabarabran (in north-west New South Wales) and I would be moved to schools near each other, my wife was moved to Bankstown Girls’ High and I to Homebush Boys’ High, both in Sydney. The schools were fairly near each other, but a long way across the city from where we lived, meaning an hour and half’s driving twice a day: but I guess, from the Department’s point of view, beggars can’t be choosers.

Three years of the Broken Hill culture did not prepare me well for the conservatism and lack of sense of humour at the Sydney schools. Though I did get to teach one senior class, I found the greater level of aggression quite depressing. Partly due to the sense of competition built in to Sydney culture, but even more because of the nature of single-sex boys’ schools, classroom teaching was not exciting for this year.

Drama could be found, but not of my kind at Drummoyne. I was immediately in strife since the young – hardly radical – men teachers and bank officers in Broken Hill had established the costume of shorts and long socks for work. My new Principal promptly informed me that only the Physical Education teacher was allowed to wear shorts, despite the heat and humidity of late summer in Sydney. But irony is always around the corner. The only subjects I was allocated to teach were English and ... PE! I still couldn’t wear shorts without time to change between 40-minute periods but, since I had never been trained to teach PE and was seriously concerned that I didn’t have the techniques to keep somersaulting teenagers safe, I conducted a term’s course in yoga.

The connection with drama might seem vague, but I had found that yoga breathing and concentration had been useful in the wings before going on stage. So my Drummoyne boys may not have gained much from PE, but I had the opportunity to explore more about yoga and to design exercises – which I hope also helped reduce a little of the city aggression. But, although I was transferred when we married without being consulted, I was glad: one term at Drummoyne was more than enough.

Homebush offered me a chance, as luck would have it, to take part in two drama events. The help Mr. Deamer gave in the production of the opera [The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay in the Benjamin Britten version]was greatly appreciated – we thank him and wish him all the best for his stay in Canada wrote students J. Lalchere and L. Pater in the school magazine, in which I am listed in the English Department.

In

fact, Tom Deamer did as many Australian teachers did: went to Canada

where higher remuneration was the icing on the cake of adventure.

Others I knew came back only in the mid-1970s, after the Federal

Government under Gough Whitlam made a major effort to inject funds into

the school systems, constitutionally the responsibility of impecunious

or stingy State Governments. I took over Tom’s plans for a shortened

version of The Beggar’s Opera to be performed for age pensioners and

hospital patients. The logistics of touring – even only to half a dozen

venues – in between teaching a full load was a major commitment.

However it did mean some escape from supervising sport on Thursday afternoons, and for me was the precursor to negotiations for theatre production to be a legitimate alternative to competitive sports, which I finally achieved in Canberra ten years later.

Then I had a call from Don Hammond. Could I please help?

Don was now the producer, seconded by the Department, of the upcoming Metropolitan Western Area High Schools Drama Festival. Could I get myself seconded to be the Lighting Designer and Stage Manager? Please!!!

At least being in Sydney meant I was close to Head Office – a bonus after all. I made an appointment to see Dan Dempsey who had long been the Supervisor of Speech and Drama. Hopefully, he would have forgotten my name since I had failed his audition to perform Shakespeare on the steps of the War Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park in my final year as a student at North Sydney Boys’ High, 1957. He had told me I would never be an actor.

If he remembered, he said nothing about that little disaster, and was obviously very keen to see the Western Area Drama Festival succeed. He wrote what was effectively an instruction to the Homebush High Principal to release me for two weeks, even though Homebush was not in the Metropolitan Western Area. At Homebush the Deputy Principal effectively ran the school, and I had seen even senior boys waiting outside his office in tears as he prepared to cane them. How would he take Dempsey’s letter?

Once again I was lucky that the Principal must have decided that the good will of an officer of Dempsey’s standing in the Department was of more value to him than following his Deputy’s advice. In tones of great begrudgement, I was more or less told I was a traitor to his school but, after all, he really had no choice.

Off I went for a new adventure – and another bout of learning the ropes of stage production, this time in a festival format, where teachers and their lively drama stalwarts would arrive for one rehearsal, no real lighting or sound check, and in need of a stage manager who could find pronto any sort of props they might need, give them advice about blocking, take over supervising their technical ‘experts’ and set them up as operators, and do it all again for another group half an hour later. It was all so full on that I can’t remember anything about the shows now.

But Don Hammond was happy – and my name in the Department had a little more caché, perhaps.

In the interval I passed my MA Qualifying having attended two evening seminars a week (in university term times) and presenting a short essay on Samuel Beckett. A central quote I used in my theme was where Estragon and Vladimir decide to abuse each other to keep from being bored.

They begin with Moron!, Vermin!, Abortion!, Morpion!, Sewer-rat!, Curate! and Cretin!

Then it’s Estragon (with finality): Crritic!

And Vladimir: Oh! and “He wilts, vanquished, and turns away”.

Maybe it was a warning for, after retiring from full-time teaching, I became a theatre critic. I always felt humbled by Beckett’s venom, and took care to write fair comment.

So this year-long interval was nearly over. Family needs were pressing. I was accepted by Sydney University for the MA by thesis course, so that I did not need to live in Sydney: I could research during the school vacations, send chapters by mail to my supervisor, and meet occasionally if there were problems. So we were on the move to the Central Coast north of Sydney, about halfway to Newcastle. The next seven years I taught at Wyong High.

However it did mean some escape from supervising sport on Thursday afternoons, and for me was the precursor to negotiations for theatre production to be a legitimate alternative to competitive sports, which I finally achieved in Canberra ten years later.

Then I had a call from Don Hammond. Could I please help?

Don was now the producer, seconded by the Department, of the upcoming Metropolitan Western Area High Schools Drama Festival. Could I get myself seconded to be the Lighting Designer and Stage Manager? Please!!!

At least being in Sydney meant I was close to Head Office – a bonus after all. I made an appointment to see Dan Dempsey who had long been the Supervisor of Speech and Drama. Hopefully, he would have forgotten my name since I had failed his audition to perform Shakespeare on the steps of the War Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park in my final year as a student at North Sydney Boys’ High, 1957. He had told me I would never be an actor.

If he remembered, he said nothing about that little disaster, and was obviously very keen to see the Western Area Drama Festival succeed. He wrote what was effectively an instruction to the Homebush High Principal to release me for two weeks, even though Homebush was not in the Metropolitan Western Area. At Homebush the Deputy Principal effectively ran the school, and I had seen even senior boys waiting outside his office in tears as he prepared to cane them. How would he take Dempsey’s letter?

Once again I was lucky that the Principal must have decided that the good will of an officer of Dempsey’s standing in the Department was of more value to him than following his Deputy’s advice. In tones of great begrudgement, I was more or less told I was a traitor to his school but, after all, he really had no choice.

Off I went for a new adventure – and another bout of learning the ropes of stage production, this time in a festival format, where teachers and their lively drama stalwarts would arrive for one rehearsal, no real lighting or sound check, and in need of a stage manager who could find pronto any sort of props they might need, give them advice about blocking, take over supervising their technical ‘experts’ and set them up as operators, and do it all again for another group half an hour later. It was all so full on that I can’t remember anything about the shows now.

But Don Hammond was happy – and my name in the Department had a little more caché, perhaps.

In the interval I passed my MA Qualifying having attended two evening seminars a week (in university term times) and presenting a short essay on Samuel Beckett. A central quote I used in my theme was where Estragon and Vladimir decide to abuse each other to keep from being bored.

They begin with Moron!, Vermin!, Abortion!, Morpion!, Sewer-rat!, Curate! and Cretin!

Then it’s Estragon (with finality): Crritic!

And Vladimir: Oh! and “He wilts, vanquished, and turns away”.

Maybe it was a warning for, after retiring from full-time teaching, I became a theatre critic. I always felt humbled by Beckett’s venom, and took care to write fair comment.

So this year-long interval was nearly over. Family needs were pressing. I was accepted by Sydney University for the MA by thesis course, so that I did not need to live in Sydney: I could research during the school vacations, send chapters by mail to my supervisor, and meet occasionally if there were problems. So we were on the move to the Central Coast north of Sydney, about halfway to Newcastle. The next seven years I taught at Wyong High.

ACT TWO: Finding My Way 1967-73

Scene Locations:

Wyong High School

Wyong Drama Group

In the early 1960s, influenced by having seen Merce Cunningham, I had once briefly attended a dance class, with Margaret Barr, the then lecturer in movement at NIDA. Then at a summer school I had had a week’s classes with her on movement and improvisation based on animal forms and internalising imagery. She was introduced in an ABC Radio National Hindsight program as

…an extraordinary woman [with a] commitment to dance and social justice - the choreographer and teacher Margaret Barr. After training in New York with the pioneer of modern dance, Martha Graham, and working at the famous Dartington Hall in England, Margaret Barr founded a dance-drama group in Sydney in 1953.

She created over sixty works that engaged with the widest cultural concerns of the day - from the Vietnam War to the poems of Judith Wright, from the hardships of rural life to the excitement of the Melbourne Cup. Margaret Barr was also director of movement at the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) for twenty three years, but the political nature of her productions often put her at odds with the dance establishment. Drawing on interviews she gave before her death in 1991, and accounts from dancers, friends, critics and historians, this feature portrays the life of an individual who believed in the power of art to change the world, and the necessity for dance to communicate a social message.

(http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/hindsight/margaret-barr/3424224)

My brief encounter with Margaret Barr (I have always referred to her by her full name in recognition of the strength of her character and intensity of her teaching) was far more influential for my drama teaching than you might expect. She gave me two basic principles to work from, which were confirmed by Broken Hill’s 1K: that movement is the basis of drama (rather than text); and that imagery is the core of emotion. “Imagery” does not only refer to visuals, but to any of the other four senses – touch, sound, taste, smell – plus the sixth sense called the kinaesthetic which tells us where parts of our bodies are in space.

At another summer school another significant teacher from an earlier generation, Eunice Hanger from the University of Queensland, had taught writing, using the image of opening doors to reveal what was to be found behind them. I found the idea fascinating because it allows you, as you write, not to know beforehand what will be discovered. Yet, the story you write falls into place, with a beginning, middle and end. At this point you can close the door, and return to real life.

(http://australianplays.org/playwright/CP-hanger)

(http://trove.nla.gov.au/people/481427?c=people)

Thus imagery also became central to my work teaching drama, but it took me years of experimenting, failures and partial successes, and a change of employment from one jurisdiction to another, before I understood how to put the idea into practice.

By the time I arrived at Wyong High in 1967, I was beginning to appreciate that there was much, much more for me to learn about the process of acting. My major undergraduate study in Psychology raised ideas about internal mental processes and external behaviour; while my minor study of Philosophy, and an interest in the nature of religions which had led me to Zen and Yoga (in company with many others in the 1960s) also took me into concerns about the distinctions between fact and fiction, reality and imagination, being in reality and being an actor.

Wyong High School

Wyong Drama Group

In the early 1960s, influenced by having seen Merce Cunningham, I had once briefly attended a dance class, with Margaret Barr, the then lecturer in movement at NIDA. Then at a summer school I had had a week’s classes with her on movement and improvisation based on animal forms and internalising imagery. She was introduced in an ABC Radio National Hindsight program as

…an extraordinary woman [with a] commitment to dance and social justice - the choreographer and teacher Margaret Barr. After training in New York with the pioneer of modern dance, Martha Graham, and working at the famous Dartington Hall in England, Margaret Barr founded a dance-drama group in Sydney in 1953.

She created over sixty works that engaged with the widest cultural concerns of the day - from the Vietnam War to the poems of Judith Wright, from the hardships of rural life to the excitement of the Melbourne Cup. Margaret Barr was also director of movement at the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) for twenty three years, but the political nature of her productions often put her at odds with the dance establishment. Drawing on interviews she gave before her death in 1991, and accounts from dancers, friends, critics and historians, this feature portrays the life of an individual who believed in the power of art to change the world, and the necessity for dance to communicate a social message.

(http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/hindsight/margaret-barr/3424224)

My brief encounter with Margaret Barr (I have always referred to her by her full name in recognition of the strength of her character and intensity of her teaching) was far more influential for my drama teaching than you might expect. She gave me two basic principles to work from, which were confirmed by Broken Hill’s 1K: that movement is the basis of drama (rather than text); and that imagery is the core of emotion. “Imagery” does not only refer to visuals, but to any of the other four senses – touch, sound, taste, smell – plus the sixth sense called the kinaesthetic which tells us where parts of our bodies are in space.

At another summer school another significant teacher from an earlier generation, Eunice Hanger from the University of Queensland, had taught writing, using the image of opening doors to reveal what was to be found behind them. I found the idea fascinating because it allows you, as you write, not to know beforehand what will be discovered. Yet, the story you write falls into place, with a beginning, middle and end. At this point you can close the door, and return to real life.

(http://australianplays.org/playwright/CP-hanger)

(http://trove.nla.gov.au/people/481427?c=people)

Thus imagery also became central to my work teaching drama, but it took me years of experimenting, failures and partial successes, and a change of employment from one jurisdiction to another, before I understood how to put the idea into practice.

By the time I arrived at Wyong High in 1967, I was beginning to appreciate that there was much, much more for me to learn about the process of acting. My major undergraduate study in Psychology raised ideas about internal mental processes and external behaviour; while my minor study of Philosophy, and an interest in the nature of religions which had led me to Zen and Yoga (in company with many others in the 1960s) also took me into concerns about the distinctions between fact and fiction, reality and imagination, being in reality and being an actor.

|

| The Ensemble Theatre, Sydney originally a boatshed. |

|

| The Ensemble Theatre - in the round https://www.ausleisure.com.au/images/ausleisure/files/Ensemble_Theatre_Sydney_1.JPG |

Hayes Gordon (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hayes_Gordon),

founder and director of the Ensemble Theatre in Sydney, developing his

own approach to the Stanislavski method, became the third highly

influential figure from an earlier generation in my next seven year

search for bringing Drama into the curriculum fold. But the

practicalities of teaching English and History in classes ranging from

Year 7 to Year 12, and from slow learners to Level 1 Matriculation, and

being Careers Adviser, while also researching and writing a thesis,

placed Drama into the slow lane of new understanding.

That didn’t mean the slow lane wasn’t very busy. I performed, directed and teched for the Wyong Drama Group, which I also chaired for some time. As in Broken Hill, the local theatre group provided contact and friendship with people from across the community, including parents whose children I was teaching. The school Drama Club and the Wyong Drama Group were closely linked by a group of three or more teachers presenting stage productions under both auspices.

That didn’t mean the slow lane wasn’t very busy. I performed, directed and teched for the Wyong Drama Group, which I also chaired for some time. As in Broken Hill, the local theatre group provided contact and friendship with people from across the community, including parents whose children I was teaching. The school Drama Club and the Wyong Drama Group were closely linked by a group of three or more teachers presenting stage productions under both auspices.

But at least, maybe I could say at last, four years’ previous experience made effective teaching much more likely to happen in my classrooms; and especially welcome was the attitude of Bob Goldie, long-term senior teacher and later deputy principal, who took the view that the younger staff coming through should be taking the senior students through the new process of matriculating under the Wyndham Scheme. I could feel more like a youthful but adult professional working in his orbit.

The Department was little changed, but I was able to make approaches and find more reasonable responses – until my last inspection in New South Wales in 1973.

The essence of Hayes Gordon (1920-1999) is well expressed in his book Acting and Performing (Ensemble Press, Sydney 1992), but the thing to remember is that around 1970 when I took students from Wyong to the Ensemble Theatre to see Hayes run a demonstration rehearsal, as well as see the evening’s performance, the finished book was nearly twenty years away. He passed the directorship of the Ensemble to Sandra Bates in 1986, only then finishing the text of his book in 1987.

I was keen to show students the quality and life of the Ensemble productions which I had found fascinating. The in-the-round layout made Sean O’Casey’s The Shadow of a Gunman especially powerful. Directed by James Upshaw, with a set consisting of no more than suspended window frames and a door frame to represent the upstairs room, I found being seated in the front row near one ‘window’ almost an invasion of the characters’ privacy. But how much more affecting it was when I sat barely a metre in front of the actress in tears as she looked down, through the ‘window’ and straight through me, to see Minnie being shot in the crossfire in the street below.

In the English classroom, all these influences meant not only should the furniture be moved, as I had done in the beginning in Broken Hill, but that drama should be a physical and emotional experience, especially for younger teenagers, rather than an intellectual study of text as it had been for me as a student in the 1950s. Yet, even then, at Enfield Grammar School in London, in Form 2 (Year 8) in the year before my parents took me to Australia, I had performed in an excerpt from Henry IV as Prince Hal. It was still a reading and fairly static, but it was on a stage with others from the class as an audience. I can say nothing about the quality of that production, but I can clearly remember the feeling of pride and sense of expressing myself to an audience.

Fortunately in the early period at Wyong High, several of us with an interest in drama had ‘home’ rooms in a group at the end of a corridor on the upper floor. This was my first experience of a home room, meaning I stayed there for almost all my classes. The students, who had different teachers for each of their subjects, had a five-minute changeover time between periods (still only 40 minutes) to move to their next teacher. This system was not maintained throughout my seven years there, as the school grew when more people moved into the area and commuted by train or the new F3 freeway to Sydney for work. The Central Coast became known as a dormitory suburb since many workers only had time to sleep there between hours of travel and work.

I, and my colleagues, found the home room congenial – provided yours was near another drama type who didn’t mind performances going on across the corridor, acoustically made more difficult by the rooms having open louvres into the corridor for ventilation. The result was a kind of excited pandemonium, and a tendency for more conservative teachers to demand home rooms at the other end of the school, or at least downstairs.

At this time the Wyndham Scheme was still coming to grips gradually with the move away from dictatorially planned lessons with strictly controlled content, towards more freedom for each teacher and their colleagues, even within one subject and year level, to provide for the particular needs of their classes. For example, Year 8 History studied the Renaissance. One class I taught had a mix of abilities from very ‘Ordinary’ to extremely ‘Advanced’, because History was an option timetabled on the same line as other subjects such as Geography, Industrial Arts or French.

My solution was drama, taking 1K as my example. While the Advanced group were working independently in the library researching topics such as the relationship between the Church and the State in Europe in the 16th Century, the Ordinary group played out Spanish and English pirate stories of exploration and conflict leading to the Armada of 1588.

After Year 10, Advanced, Credit and Ordinary became Levels 1, 2 and 3. In one English class I discovered that a number of students whose previous results showed they were likely to succeed at Level 2, or even some at Level 1, had enrolled in Level 3. In the late 1960s and early 1970s the old Australian ‘tall poppy syndrome’ was still a strong cultural influence, especially in country areas. Part of the Level 3 curriculum was for the students to study aspects of media – print and television.

The nearest I could get to drama in this case was for small teams to create their own advertisements. I didn’t have the technology available to make video recordings, but I asked the students to make up ideas as storyboards so that they would take the study further than static newspaper or magazine ads. The key to making this study experiential (a word which made it into the regular lexicon in the 1980s) was to take the class to a well-known advertising agency in Sydney for some reality assessment.

It wasn’t long before the higher ability students realised how the advertisers were attempting to manipulate their audience’s attitudes and feelings, when the agency – after giving highly positive judgements about the student’s presentations – took us into a studio to show us one of their new productions. They asked the students what they thought about the ad, but what those with Level 1 potential noticed was how the agency staff watched and noted the students’ reactions while being shown the movie. From our discussions back in the classroom I am fairly confident that several students learnt to analyse what they were seeing on television, and some degree of cynicism developed.

But, after all, one aim of the English course was to develop critical thinking!

Getting drama into the classroom in its own right was not going to happen easily, because suitable timetabling, rooming and anything like theatre facilities were simply not thought of when the school was built. There was not even an assembly hall or gym. As the population of the Central Coast increased, a new wing of classrooms was added. Once again I tried moving the furniture.

One requirement of the new building was to include a GA Suite. This was supposed to be for those classes below 1K, remembering my Broken Hill experience, called General Activity, on the assumption that such low-IQ children would need more floor space than the standard for normal children. At the same time, since the school population was changing as well as increasing, something flexible was needed. The answer was to have three rooms separated by heavy sound-insulated concertina walls. With some (in fact quite considerable) effort, you could have three separate rooms, or one standard plus a double size room, or even a triple size room. I thought there had to be some way I could use this arrangement.

I had to engineer not just the physical space, of course, but the mental space of my senior teacher. There were two steps in this process. First I had to propose that the English weekly program could be restructured from the convention which had been the norm since I had first attended secondary school in 1952.

Each English period each week was dedicated to one genre: poetry, short story/novel, drama, and language. Fortunately, under the auspices of a mature radical senior teacher like Bob Goldie and with support from the other young radicals, I successfully lobbied to be allowed – in only one of my classes, and only for one term – to teach each genre for a week’s lessons in a row, so that over a four week period each genre received the same teaching time.

Timetabling and rooming came next. There was usually a need for some classes to have a double-length class, especially as the Wyndham Scheme had encouraged a wider variety of courses to be available for a greater proportion of the clientele. Timetabling had become so unpredictable by this time at Wyong that only after the new staff and students had arrived for each year could the timetable be worked out – often taking a week or two to finalise. It was in this chaotic gap that I was able to have one class (in Year 9) allocated a double room in the GA Suite. For standard English lessons I could use one room with desks, but for drama I could open up the concertina wall and move furniture to one side to make a drama space.

Fortunately for my sanity and reputation, this arrangement only lasted one 14 week term. By this time, 1971, I had picked up some ideas from watching Hayes Gordon rehearse which distilled down to ‘improvisation’. I thought that asking the students to improvise acting out scenes that they invented would release their creativity and produce wonderful performances. I did have some idea about ‘warming’up’.

Quite a lot of warming up happened while the furniture was stacked aside, only to reveal an open area of very new highly polished floor. Of course I had asked the students to remove their shoes, and within a few seconds sliding across the shiny surface became an extended warm-up – at first in their socks, and before long on their backs. It was great fun, though it sometimes turned into a potentially dangerous competition as some became handlers, flinging a partner willy-nilly across the floor. I could see some loosening up was taking place – it was certainly done with a sense of freedom not normally seen in the classroom – but I had only seen warm-up and improvisation take place among already experienced and disciplined adults.

I hadn’t expected this kind of ‘behaviour’ which looked like very large kindergarten children going berserk. I was trained as a secondary teacher, so I had no skills in setting up the sorts of rules and signals that early childhood teachers knew to control young children’s impulse for constant movement. I had expected Year 9 to be hesitant about being on an open floor, a bit like having stage fright that I had experienced in the theatre. What I hadn’t thought of was that in this situation there was no audience to judge them, except perhaps me – but, except again, that I had apparently given them unlimited freedom.

Some sort of intuition took me to where any kindergarten teacher would have begun, and some kind of ragged circle formed. But now what should I do? I had no training and little experience for working drama with teenagers, let alone these ratbags. I couldn’t get angry with them, of course, because that wouldn’t be fair. The only practical step that I could hope might work was to have a small group perform a skit for the others to watch and respond to.

As 1K, in Year 7, had shown me, this could develop into something worthwhile, though there was always the risk that it wouldn’t. I also had memories of a successful effort with Year 7 when I had been practice teaching at Normanhurst Boys’ High in Sydney in 1962. The class was reading Wind in the Willows, so I took them out into the wooded grounds of the school, divided them into six small groups, sent each group off to work out a playlet drawn from one part of the story, and had them return and perform the whole story in six parts. Of course I was barely passed by the Teachers’ College supervisor, since he had turned up to find my classroom empty and had to search the grounds to find me.

But suggestions of this kind did not work with Year 9. Skits hardly developed beyond imitations of tv ads or a couple of family arguments. Where was the depth that I had been looking for since reading Eugene O’Neill? Not in Wyong, apparently.

After another attempt in the second week, I had no choice but to abandon the idea and return to the conventional 40 minutes per genre English classes. It was a significant failure on my part which I could hardly discuss with teaching colleagues, not even the ones who had become real friends.

I wasn’t sorry when even the time-tabling and rooming had to change for the next term.

Barry Payne, Howard Cassidy, Heather Brown, Jim Saunders and I formed the core group of teachers who combined our personal interests in theatre with our desire to teach drama. In Wyong Drama Group we wrote, directed, acted, stage managed and teched. We directed school productions in a close relationship with the WDG, whose members at times included high school students and parents. As in Broken Hill, my relationship with the local community was almost as much a part of my teaching as my work in the school, and I continued to work in this vein until, indeed even after, my formal retirement.

In Broken Hill, though, my involvement in the Repertory Theatre was essentially separate from the business of teaching. Now, with a coterie of teachers with the same interests, my work both in the Drama Group and with the students began to coalesce. Working on plays like Mother Courage and her Children, Rhinoceros, The Crucible, and Mourning Becomes Electra (Eugene O’Neill!) with the school group was not too different from working on Arms and the Man, The Glass Menagerie, and She Stoops to Conquer in the Drama Group.

Light relief came from WDG productions like Love’s a Luxury, and Central 2000. This has been recorded on the website as a revue for eight players with a view to the CENTRAL COAST in the year 2000 a.d. It's interesting to note that the term "Central Coast" existed in 1969, and we can see how accurate they were with sketches like "Hospital Call" calling for a hospital at Wyong, which finally opened in 1980, not beyond 2000 as implied by the call. The revue was produced by Barry Payne.

The writing credits go to Frank McKone (for "Concrete", "Races" and "Prawner") Howard Cassidy (for "Hound" and "Milking") and Barry Payne himself (the rest - ie MOST of the revue).

These photos may give some idea about the show:

These

costumes represent prawns, as found in the Tuggerah Lakes. The

punchline for the Prawn Lake Ballet was "don't come the raw prawn with

me". Of course it was built up over a while... George Geatches, Heather

Brown, Jim Saunders & Ann Cassidy coming the raw prawn with all of

us.

Howard Cassidy holds a swimming Frank McKone in the Prawn Lake Ballet.

And

yet, of course, I was not ‘teaching’ drama. What, from my point of

view was not just fun, had no formal recognition. The community

involvement was ‘personal’ and productions with students were

‘extra-curricular’.

Yet how could it be that the school would give me permission and time off to take students ‘on excursion’ to the Ensemble Theatre, or to the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s recording studios in Sydney as I did with the group working on The Crucible?

Why had Dan Dempsey been so keen to see schools take part in a two-week long drama festival back in 1966? And why, as I discovered at Wyong High, was the principal very happy for me to top up the school’s finances with box office income from student productions, while costs were left to the participants?

What was in it for the school system?

As many others found out, it was about prestige and reputation. The school and the Education Department took the credit, but the individual teacher was given little in return – though I have to say that I still value the support that students and community people gave me over many years. I still occasionally receive heart-warming phone calls and emails from the now long distant past. A very special occasion was the 50th reunion of students from the 1968 Year 12, organised by Chris Gavenlock, which I and Howard Cassidy attended. We read back to them the poetry they had written for the school magazine for which I had been the editor. In 2018 they were as impressed with the depth of the feelings and understanding they had shown, as we had been in 1968.

On 1 October 1968 the first strike action by teachers in New South Wales took place. One of the issues particularly interested me. We demanded clerical staff to support our work as teachers. Politicians and the general community were so surprised that we won much of what we demanded after just one day on strike.

My concern was that I had no access to the school accounts. What happened to the money we collected at the box office? If we had a proper bursar rather than the Principal’s secretary, perhaps I could negotiate a budget for stage productions.

This certainly was unlikely with a series of principals who regarded the school as their personal fiefdom, and not surprisingly it didn’t come to pass at Wyong High. But it set me thinking about the future. In the meantime, productions with students became a tradition of serious work, beginning with Barry Payne’s staging of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and her Children.

Working on this play in the political atmosphere of the time – not only union action like ours, but the protests against the war in Vietnam and events in Paris, as well as the shooting of students at Kent State University – took us into a new level of education in conservative New South Wales. For the senior students the sorts of issues in Mother Courage were real. Among the Year 12s, now turning 18 and becoming adults while still at school, I remember a couple who deliberately started a pregnancy, so that their parents would accept their marrying before the young man was sent to Vietnam. He had been selected by the lottery system based on birthday dates as he turned 18, and his wife was determined to make sure she would at least have his child if he failed to return.

Directing, designing and performing Brecht was not a simple matter. None of us had enough background to properly appreciate how to make the ‘alienation effect’ work, but one scene silenced the Wyong Memorial Hall: Scene 11. However much Brecht may have wanted the audience to ‘understand’ through being ‘distanced’ from ‘sentimental’ emotion, our audience was overwhelmed by Kattrin’s self-sacrifice to save the village below. Her drumming on the roof-top focussed attention absolutely. The single gun shot as she wept and died sent a shock wave throughout the hall. At last, I could see the possibility of really teaching drama. Yet there were risks I was barely aware of – for the girl who played Kattrin.

I guess the central issue for teenagers, in my experience from about Year 8 and increasing in intensity as the Years go on, is Who Am I? The key feature of this question is emotional sensitivity. For most kinds of teaching, what the student is feeling is set to one side in the quest for critical thinking, objective analysis, logical argument and even simple ‘common sense’. This is the language of the modern scientific approach to life, which has stood us in good stead economically and socially as the philosophy of humanism has gradually spread – and continues to fitfully spread – throughout the world since about 1500.

Teaching, or perhaps let me say ‘enjoying’, the arts in schools is not about denying or opposing the scientific method. But the arts are essential in schools to provide for the personal development of people to balance the impersonal. In adult life we need both. If there was ever one playwright who understood this, it was William Shakespeare. Drama is not the only necessary artform, but think about why his works – as literature and in performance – are such a powerful force today not only in traditionally English-speaking parts of the world but in every nook and cranny where theatre takes place, on stage, screen or audio.

Acting is experiencing, enacting and creating feeling. In my seven years at Wyong High School, starting from observing the girl who played Kattrin, I bit by bit began to become aware of the effects of playing roles of great emotion.

My own acting, as you may have observed from my playlist, was essentially light-weight amateur, in comedies. Nothing too demanding there. And yet playing the incompetent Scoutmaster in Love’s a Luxury gave me some insight into the experience of playing Kattrin, and especially later for the girl who played Mary Warren in The Crucible, and even later for the girl who played Lavinia in Mourning Becomes Electra.

Yet how could it be that the school would give me permission and time off to take students ‘on excursion’ to the Ensemble Theatre, or to the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s recording studios in Sydney as I did with the group working on The Crucible?

Why had Dan Dempsey been so keen to see schools take part in a two-week long drama festival back in 1966? And why, as I discovered at Wyong High, was the principal very happy for me to top up the school’s finances with box office income from student productions, while costs were left to the participants?

What was in it for the school system?

As many others found out, it was about prestige and reputation. The school and the Education Department took the credit, but the individual teacher was given little in return – though I have to say that I still value the support that students and community people gave me over many years. I still occasionally receive heart-warming phone calls and emails from the now long distant past. A very special occasion was the 50th reunion of students from the 1968 Year 12, organised by Chris Gavenlock, which I and Howard Cassidy attended. We read back to them the poetry they had written for the school magazine for which I had been the editor. In 2018 they were as impressed with the depth of the feelings and understanding they had shown, as we had been in 1968.

On 1 October 1968 the first strike action by teachers in New South Wales took place. One of the issues particularly interested me. We demanded clerical staff to support our work as teachers. Politicians and the general community were so surprised that we won much of what we demanded after just one day on strike.

My concern was that I had no access to the school accounts. What happened to the money we collected at the box office? If we had a proper bursar rather than the Principal’s secretary, perhaps I could negotiate a budget for stage productions.

This certainly was unlikely with a series of principals who regarded the school as their personal fiefdom, and not surprisingly it didn’t come to pass at Wyong High. But it set me thinking about the future. In the meantime, productions with students became a tradition of serious work, beginning with Barry Payne’s staging of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and her Children.

Working on this play in the political atmosphere of the time – not only union action like ours, but the protests against the war in Vietnam and events in Paris, as well as the shooting of students at Kent State University – took us into a new level of education in conservative New South Wales. For the senior students the sorts of issues in Mother Courage were real. Among the Year 12s, now turning 18 and becoming adults while still at school, I remember a couple who deliberately started a pregnancy, so that their parents would accept their marrying before the young man was sent to Vietnam. He had been selected by the lottery system based on birthday dates as he turned 18, and his wife was determined to make sure she would at least have his child if he failed to return.

Directing, designing and performing Brecht was not a simple matter. None of us had enough background to properly appreciate how to make the ‘alienation effect’ work, but one scene silenced the Wyong Memorial Hall: Scene 11. However much Brecht may have wanted the audience to ‘understand’ through being ‘distanced’ from ‘sentimental’ emotion, our audience was overwhelmed by Kattrin’s self-sacrifice to save the village below. Her drumming on the roof-top focussed attention absolutely. The single gun shot as she wept and died sent a shock wave throughout the hall. At last, I could see the possibility of really teaching drama. Yet there were risks I was barely aware of – for the girl who played Kattrin.

I guess the central issue for teenagers, in my experience from about Year 8 and increasing in intensity as the Years go on, is Who Am I? The key feature of this question is emotional sensitivity. For most kinds of teaching, what the student is feeling is set to one side in the quest for critical thinking, objective analysis, logical argument and even simple ‘common sense’. This is the language of the modern scientific approach to life, which has stood us in good stead economically and socially as the philosophy of humanism has gradually spread – and continues to fitfully spread – throughout the world since about 1500.

Teaching, or perhaps let me say ‘enjoying’, the arts in schools is not about denying or opposing the scientific method. But the arts are essential in schools to provide for the personal development of people to balance the impersonal. In adult life we need both. If there was ever one playwright who understood this, it was William Shakespeare. Drama is not the only necessary artform, but think about why his works – as literature and in performance – are such a powerful force today not only in traditionally English-speaking parts of the world but in every nook and cranny where theatre takes place, on stage, screen or audio.

Acting is experiencing, enacting and creating feeling. In my seven years at Wyong High School, starting from observing the girl who played Kattrin, I bit by bit began to become aware of the effects of playing roles of great emotion.

My own acting, as you may have observed from my playlist, was essentially light-weight amateur, in comedies. Nothing too demanding there. And yet playing the incompetent Scoutmaster in Love’s a Luxury gave me some insight into the experience of playing Kattrin, and especially later for the girl who played Mary Warren in The Crucible, and even later for the girl who played Lavinia in Mourning Becomes Electra.

|

| The Scoutmaster in Love's a Luxury |

The

connection was fear. My Scoutmaster had to front up to the Figure of

Most Importance in the village society, knocking at the knees (which I

could do visibly to great effect), causing great gusts of laughter. I

was then dismissed off stage, only to have to return in a later scene

having proved to the utmost the judgement made previously by the FMI

that I was incompetent. Fearful though I had been in that scene, now I

had to face something like a Tyrannosaurus Rex ready to devour me

(played incidentally by a well-known Wyong lawyer, at the time the

President of the Wyong Drama Group, and a real Figure of Most Importance

in that town.) Rather than knock my knees even louder, I tried a

little of the so-called American Method, made famous by Lee Strasberg,

to make myself believe I was really afraid.

The result was electric with laughter for the audience, but the electricity remained in my emotional system for the rest of the evening, even though that scene was my last appearance. It was actually quite hard to go on for a happy and relaxed curtain call. I was still feeling ‘in character’.

You will also have noticed that much of my stage work was as a technician, mostly in lighting. Even in early childhood my family and others had seen me as an observer rather than as a pure participant. Later in life my personality became at least seen as introspective, even if not introverted. I had often thought of myself as just shy. The great thing about lighting a play is that you learn to watch everything very closely as you wait for the right moment to operate the next cue.

Watching these three girls, I could begin to see when they were ‘in character’ and when they were not. The risk of not coming out of character was something I learned to watch for. But it’s not easy to tell. ‘Kattrin’ played her self-sacrifice very much in character, even as she was carried off in death. She represented her fear through her drumming, steadfastness and fixed determination, took the audience with her (in a large rectangular multi-purpose hall), and was justifiably proud of her achievement at the curtain call only a few minutes later after the short Scene 12. But did I really know how she felt?

At the time I felt satisfied with what we teachers had done to bring about such maturity of performance in a school production. It was a feather in our cap to have students take on and successfully create ‘adult’ theatre.

While rehearsing The Crucible after hours one evening, Abigail and the girls who see the spirit-bird in the rafters, screamed with such intensity and sincerity in their belief that a cleaner came rushing upstairs to help with the emergency. But in the play, Mary Warren is not sure of her position, knowing that the girls are really only acting on Abigail’s instruction, while being mortally afraid of Abigail’s destructive power. Acting such a character by a Year 9 girl about the same age, with such conflicting emotions, was a major achievement in my eyes. The production was seen as a great success by the audience, largely of parents, because they could see the learning and the development that had taken place in their children, through the engagement with Arthur Miller’s work.

Again I was content.

But two weeks later some of the other girls in the cast came to tell me that ‘Mary Warren’ had been fearful and found that she couldn’t concentrate on other schoolwork – in fact that she had only just by then found her way out of ‘character’, with a lot of support from her friends.

My mistake.

The ending of Mourning Becomes Electra is deeply depressing. Set on the front steps of a Southern States mansion, we painted Grecian columns on 4 foot wide flats extending upwards beyond the lighting bars to make them seem to continue to the heights of an Ancient Greek stage. The theme of the play is to reveal the disaster which is the grand delusion of the American Dream. For Lavinia, the only member of the family to survive, there is nowhere else to go.

We made the doors into the house of 12 foot high flats, monstrously huge, yet themselves seemingly nothing against the massive columns. After the deaths of her father, mother and brother, in which she has no small part, Lavinia is left, standing alone, downstage centre. In theory she has a choice to walk away, to leave the house as a mausoleum, to find a new life, to go somewhere. In that she would represent hope, possibility of change, of progress, of life.

On the other hand, she cannot escape the past and her own guilt. She turns slowly towards the steps, resolutely, step by step, away from the light, up carefully, almost in a dreamlike state. As she approaches those great doors, they seem to look down upon her. She seems to become visibly smaller as she climbs and crosses the platform. One of the double doors begins to open, just a fraction, just enough to see that all is dark inside. There is no hope, no possibility of change, no progress, no life in there.

Lavinia slips through the narrow crack in this monumental wall of cold stone. Silence. Nothing changes on stage. Lavinia has gone. That is the end.

The audience, in that same Wyong Memorial Hall, remains in silence until they can no longer stand the dread. They begin to clap, as if half-heartedly.

Backstage, the cast and crew have gathered around ‘Lavinia’ to comfort her, to wipe away her tears, and finally to enter from the wings, and stand, a small group, on the stage before that house of doom. The clapping firms until at last ‘Lavinia’ herself appears, steps forward and bows, with all the cast, in recognition of their community’s applause.

Have I made a mistake again? Is ‘Lavinia’ OK? I check with other cast members as the audience is leaving. No, she’s good, they say. As she leaves the dressing room, ‘Lavinia’ smiles and says, ‘Thank you’.

I give her two weeks, with others saying ‘No worries’, and arranged for a talk. “How do you do it?” I ask. She tells me how her parents divorced when she was 10; how they each have remarried and have had new children – and how much she enjoys her life now, age 16! “I have two homes,” she explains, “and eight grandparents. They all live in different parts of the country. They all love me and I’m never short of somewhere to stay whenever I want. What could be better than that?”

What indeed – and I often feel that, if only, I would love to tell that story of ‘Lavinia’ to Eugene O’Neill. Maybe this is the Australian Dream?

The result was electric with laughter for the audience, but the electricity remained in my emotional system for the rest of the evening, even though that scene was my last appearance. It was actually quite hard to go on for a happy and relaxed curtain call. I was still feeling ‘in character’.

You will also have noticed that much of my stage work was as a technician, mostly in lighting. Even in early childhood my family and others had seen me as an observer rather than as a pure participant. Later in life my personality became at least seen as introspective, even if not introverted. I had often thought of myself as just shy. The great thing about lighting a play is that you learn to watch everything very closely as you wait for the right moment to operate the next cue.

Watching these three girls, I could begin to see when they were ‘in character’ and when they were not. The risk of not coming out of character was something I learned to watch for. But it’s not easy to tell. ‘Kattrin’ played her self-sacrifice very much in character, even as she was carried off in death. She represented her fear through her drumming, steadfastness and fixed determination, took the audience with her (in a large rectangular multi-purpose hall), and was justifiably proud of her achievement at the curtain call only a few minutes later after the short Scene 12. But did I really know how she felt?

At the time I felt satisfied with what we teachers had done to bring about such maturity of performance in a school production. It was a feather in our cap to have students take on and successfully create ‘adult’ theatre.

While rehearsing The Crucible after hours one evening, Abigail and the girls who see the spirit-bird in the rafters, screamed with such intensity and sincerity in their belief that a cleaner came rushing upstairs to help with the emergency. But in the play, Mary Warren is not sure of her position, knowing that the girls are really only acting on Abigail’s instruction, while being mortally afraid of Abigail’s destructive power. Acting such a character by a Year 9 girl about the same age, with such conflicting emotions, was a major achievement in my eyes. The production was seen as a great success by the audience, largely of parents, because they could see the learning and the development that had taken place in their children, through the engagement with Arthur Miller’s work.

Again I was content.

But two weeks later some of the other girls in the cast came to tell me that ‘Mary Warren’ had been fearful and found that she couldn’t concentrate on other schoolwork – in fact that she had only just by then found her way out of ‘character’, with a lot of support from her friends.

My mistake.

The ending of Mourning Becomes Electra is deeply depressing. Set on the front steps of a Southern States mansion, we painted Grecian columns on 4 foot wide flats extending upwards beyond the lighting bars to make them seem to continue to the heights of an Ancient Greek stage. The theme of the play is to reveal the disaster which is the grand delusion of the American Dream. For Lavinia, the only member of the family to survive, there is nowhere else to go.

We made the doors into the house of 12 foot high flats, monstrously huge, yet themselves seemingly nothing against the massive columns. After the deaths of her father, mother and brother, in which she has no small part, Lavinia is left, standing alone, downstage centre. In theory she has a choice to walk away, to leave the house as a mausoleum, to find a new life, to go somewhere. In that she would represent hope, possibility of change, of progress, of life.

On the other hand, she cannot escape the past and her own guilt. She turns slowly towards the steps, resolutely, step by step, away from the light, up carefully, almost in a dreamlike state. As she approaches those great doors, they seem to look down upon her. She seems to become visibly smaller as she climbs and crosses the platform. One of the double doors begins to open, just a fraction, just enough to see that all is dark inside. There is no hope, no possibility of change, no progress, no life in there.

Lavinia slips through the narrow crack in this monumental wall of cold stone. Silence. Nothing changes on stage. Lavinia has gone. That is the end.

The audience, in that same Wyong Memorial Hall, remains in silence until they can no longer stand the dread. They begin to clap, as if half-heartedly.

Backstage, the cast and crew have gathered around ‘Lavinia’ to comfort her, to wipe away her tears, and finally to enter from the wings, and stand, a small group, on the stage before that house of doom. The clapping firms until at last ‘Lavinia’ herself appears, steps forward and bows, with all the cast, in recognition of their community’s applause.

Have I made a mistake again? Is ‘Lavinia’ OK? I check with other cast members as the audience is leaving. No, she’s good, they say. As she leaves the dressing room, ‘Lavinia’ smiles and says, ‘Thank you’.

I give her two weeks, with others saying ‘No worries’, and arranged for a talk. “How do you do it?” I ask. She tells me how her parents divorced when she was 10; how they each have remarried and have had new children – and how much she enjoys her life now, age 16! “I have two homes,” she explains, “and eight grandparents. They all live in different parts of the country. They all love me and I’m never short of somewhere to stay whenever I want. What could be better than that?”

What indeed – and I often feel that, if only, I would love to tell that story of ‘Lavinia’ to Eugene O’Neill. Maybe this is the Australian Dream?

Pinterest image - this production is not named. This is not my Lavinia.

This set design is similar to mine in concept, but less intimidating in its effect.

This set design is similar to mine in concept, but less intimidating in its effect.

As

always, what may seem to be a dream in one aspect – the work with the

young people and the community in the enjoyment of the arts – has its

backside. Paul Roebuck was a significant mover in the teaching service

in New South Wales towards Drama becoming a separately recognised

curriculum area, as Music and Art had been for decades. Among the moves

was the idea of specialist high schools, and I had been invited on to a

committee, which included Sandra Bates from Ensemble Theatre, in 1969,

to suggest designs for drama studios for schools specialising in the

arts. I believe Forest High, in the expanding Sydney suburb of

Forestville, was expected to be the first.

With this project in mind, and as I was completing my MA thesis on Bernard Shaw, I met with Noel Cislowski, the current Head of Speech and Drama, in his office in Sydney. I thought by this time, 1971, that I could look forward to some progress, but Noel’s response was “Don’t even think about it for at least ten years.” My response, as you have seen, was simply to get on with doing it, extracurricularly as usual.

By 1974, “Do It” had become the title of the first journal of the NSW Educational Drama Association, but by that time I was no longer teaching in New South Wales.

I began looking around for other opportunities, but one of those unfortunate twists in the fabric of the universe possibly set me back – or maybe set me on the best path for me. I completed my supposedly 3-year thesis, after being granted a year’s extension, in 1970. The formal award of the degree should then have taken place around May 1971. Busy as I was, and assuming the Sydney University administration was working normally, I realised later in the year that I had not received the documentation and had missed the ceremony. Enquiries ended up concluding that the university was not to blame. The mail had disappeared. Yet the Post Office couldn’t trace it.

At the same time, at the University of NSW, which had hosted NIDA since its inception, action was in train to establish Drama as an undergraduate course in the BA Degree. Since I now had to wait for my MA to be formally awarded until 1972, I applied to NSW and had to attend an interview without the appropriate piece of paper in hand. Recalling the interview, I am not at all confident that it would have done the trick. My MA could only be at Pass level, since I had not originally gained Honours in my BA. As well, my MA is formally in Literature, which prevented me from including the study I would have liked to make of Shaw’s plays in production. And, of course, the work had not been published at that point (nor since).

As time has moved on, I also discovered that I was never well suited to the world of competitive academia, though I had brushes with it at various times. At this particular time, a different unexpected twist presented me with an opportunity for 20 years of development of my ideas about teaching drama. A friend called me to say that he had found a way to escape the clutches of the NSW Department of Education (though in fact we were both now past the five years’ teaching which our scholarships had demanded of us). Had I realised, he asked, that the Australian Capital Territory, belonging to the Commonwealth (or Federal) Government, had made the decision to run its own education system instead of contracting out that function to the NSW Government?

No, I had not. The ACT, after a great deal of argument between the States when the Federation was established in 1901, was placed geographically between Melbourne and Sydney. The site finally chosen for Canberra turned out to be rather closer to Sydney (a little under 300kms) than Melbourne (about 800kms) and was therefore completely surrounded by New South Wales. At first the Commonwealth Government continued to sit in Melbourne until the first temporary (now known as the Old) Parliament House was built. With the intervention of the two World Wars, Canberra did not grow substantially until the 1950s as departments were gradually moved from Melbourne. It had been convenient for the Commonwealth to have NSW continue providing schools in the Territory as it had begun to do in the 1880s before federation.

Within the NSW system there was considerable jealousy and competition about being appointed to Canberra, because the Commonwealth resourced the buildings and equipment more generously, and because the establishment of the Australian National University and the influx of the upper echelons of the Public Service gave Canberra schools a high status comparable to other elite government schools in Sydney.

However now that the 1960s were well advanced, and the population increased and became more permanently settled, Canberra began to put pressure on the Commonwealth Minister for Territories to escape the clutches of a conservative Sydney-centred NSW Department of Education. An agreement was made that teachers who wanted to stay in Canberra would have that right, and that teachers leaving the NSW jurisdiction and joining the ACT would have all their leave and superannuation entitlements transferred directly to the new system. The Commonwealth set up the ACT Schools Authority as an ‘arms-length’ body, giving the local community the power to decide how it would operate. In this way teachers in the new ACT system did not become Commonwealth Public Servants with all the rights and employment transfer structure available to them. But ACT teachers were automatically members of the defined benefit Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme.

Would I consider, alongside my telephoning friend, applying for an interview? You bet. (In the event, though, he obtained a place at Griffith University in Queensland – the escape he fervently desired from school teaching.)

In my interview in 1972, about starting a new system from scratch, I made it clear (with my MA in hand by now) that I intended to establish Drama as a subject in its own right in secondary schools. I got the nod in mid-1973 to start in a brand new (in fact not yet completed) school from February 1974. But before Interval, there’s one last Wyong story to tell.

This is not a Drama story, but illustrates the quality of change as I moved out of the old and into the new.

By the early 1970s, the NSW Department was trying to come to grips with one of the consequences of the Wyndham Scheme which was ‘unforeseen’. The scheme was meant to provide more appropriate education for a wider range of children. A large proportion of children still left school without attempting matriculation but how was their educational status to be measured and described? In prior times, children left school at 14, some completing the Intermediate Certificate and leaving at the end of Year 9 (Form 3), and others going on to the Leaving Certificate to try to matriculate to university at the end of Form 5 (Year 11). This was the system I underwent, matriculating in 1957, and entering university as I just turned 17.

Wyndham extended the system to Year 12 before matriculating and looked for not only more children staying in education longer, but a wider range of abilities being catered for, for more years. So the Year 10 Certificate replaced the Intermediate, and the Year 12 Certificate replaced the Leaving. In my Leaving Year, 1957, only some 5% of the total age group cohort matriculated. But in 1972, the Federal Government elections were won by Labor, led by Gough Whitlam, after 23 years of conservative government by the Liberal and Country (later re-named National) Parties. It was time for the NSW Wyndham Scheme to prove its worth in Australian Labor Party terms.

(Purely aside, only the ALP uses the American spelling ‘labor’, while in every other situation the British spelling ‘labour’ is used – an historical anomaly.)

Trying catch up with the world moving around it, NSW had defined its children by their supposed intelligence levels – the Advanced, Credit and Ordinary system. But then how should anyone know how these children related to each other educationally? So began the belief in the ‘normal curve’.

I had begun my teaching career with a major in Psychology, including a reasonable smattering of statistics, 10 years before my final run-in with the NSW system. I had shown a staff meeting in Broken Hill how their off-the-cuff classroom tests were probably statistically invalid and certainly statistically unreliable. I knew perfectly well that statistics may be useful for describing observations and perhaps for some qualified predictions under carefully controlled conditions (which never occur in real classrooms), but it is completely inappropriate to predetermine what will happen to specified individuals. Yet this is exactly how the NSW Department began to use the idea of the ‘normal curve’, often also called the ‘bell curve’.

On the basis of IQ testing and previous results, each school was told that it could present, say, 1 class for the Advanced level in the Year 10 Certificate, 2 classes at Credit level and any others at Ordinary level. This was the situation I faced when teaching a Year 10 English class in 1973.

I had always, perhaps especially because of my Psychology background, been very keen to study what we teach, what children actually learn, and how we know what they can do as a result of what they have learned. By 1973 I had spent a good deal of time reading the recent research on the relationship between talking and writing. The research was not all as scientifically precise as one would like, but the essence that came through was that talk provided people with the opportunity to work out what they understood about a topic. If writing was required, then the writing of ideas and arguments was improved if talking the ideas through took place first. Part of the discussion of these results included the point that in the ordinary real world (in a modern literate society like Australia) it was common for talk to take up about 75% of communication time, and writing about 25%.

I considered the class I faced, without using IQ test results, and thought that, based on my now 10 years’ experience, that perhaps 75% of the group should be capable of passing the Year 10 Certificate at Advanced level. I thought that the information from the research would be useful in planning lessons, using up to 75% of the time in talk, followed up by 25% of the time used for writing based on the discussion.

But the school had been told by the Department that only one class could sit the Advanced paper. My class was regarded as the next class down, and could sit only the Credit paper.

I took the issue up with the students and parents and presented the Principal with an argument that my class should sit the Advanced paper. Anyone not passing at that level could still be expected to receive a Credit pass. In the background, though not made explicit in my discussions with senior teachers and the Principal, was that others also thought the predetermined allocation of classes to levels was unfair and the reputation of the school would be enhanced if more passed Advanced. I also wanted to prove the point that this use of statistical method was a serious misuse which could affect individuals’ future prospects.

At the same time, early in the year (not at this stage having a job confirmed in Canberra) I put a bid in to be inspected for promotion from List 1 (that is, an ordinary teacher) to List 2 (from which I could apply for Senior Teacher positions such as subject head).

As it turned out, the inspection would not be until Term 3 (in the days of the Three Term Year). As it further turned out, I received an offer of a job in Canberra early in Term 3, about two weeks before the inspection. I kept quiet about this information (though going on my previous experiences I would not be surprised if the Department already knew).

Now to the nub of the story. I had done as I planned, using the 75% talk, 25% writing approach. The students had taken a mid-year test and shown that many, if not all, were likely to do well at Advanced level, and the school (that is, the Principal) presented two classes for Advanced instead of the official one.

The inspector came as expected, walked around the room while the students worked on a writing task, asked some to show him their books. His first observation to me in his interview was that there wasn’t much written work in their books – obviously in his view they should have full to overflowing books by Term 3. Knowing my future employment situation, I decided against making the mistake I had with my very first inspector. Rather than argue my case, I said very little. However, what interested me was that he did not make a decision on the spot, which was the usual procedure. It was some ten days later before I received the notice of rejection. Perhaps it was thought they could get rid of this fly in their ointment by letting me go to Canberra.

As I duly did that December; but only after the results of the Year 10 Certificate had come out. Only one in my class did not receive an Advanced pass, receiving a Credit instead.